Keeping Down the Walls

How the Rocklin Bubble was Shattered for Me

November 4, 2016

I was chosen to be a leader for Breaking Down the Walls, and let me tell you, it may have been one of the most eye-opening experiences of my life.

I signed up to be a leader for one main reason: I am fascinated by people. In a place like Rocklin High where you are constantly swimming in a pool of 2100 other students and going to eight different classes, it is extremely difficult to see your peers as anything other than bodies filling desks. Still, I wanted to see the inner workings of those people that have sat next to me for the last three years.

Immediately upon arrival at the gym, the atmosphere was different. The doors were all closed, with 200 other kids and me inside until 2:40. The leaders were in control of 45 minutes of those seven hours, the rest of the time we were as unaware as the rest of the participants.

We began the day with light-hearted get-to-know-you games, partnering with a person we had never talked to before and discovering we both had surprisingly similar tastes in cars/sports/favorite colors/pizza toppings/etc. We would play games of tag and name games. Every time we were told to find a new partner, I always seemed to be paired with a person who I had already formed a preconceived notion of, and was always terribly, horribly wrong.

Every single time.

Soon, we got into small groups led by the dubbed leaders, doing more team-bonding games and asking surface level questions about each other.

“You like fuzzy socks too? No way! I like fuzzy socks!”

But after lunch, things got real.

Really real.

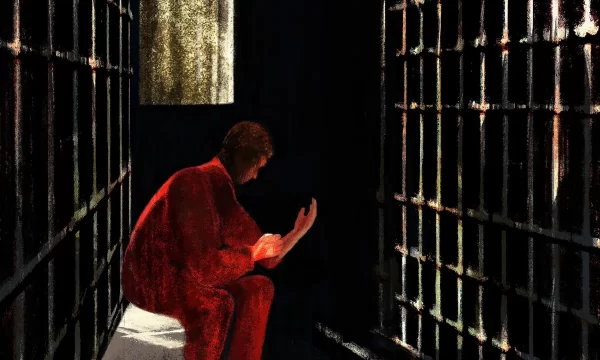

We began playing the notorious Cross the Line game which, if you know someone who partook in the program two years ago, you have probably heard stories of how emotional and heart wrenching it is.

And the stories are definitely not wrong.

The program leader Mr. Mike Walsh prefaced the activity by stressing that whatever we did– no matter how uncomfortable we felt at any given point–we were not allowed to crack jokes. This was a safe space, and cracking a joke would poke holes at that safety bubble.

Once again, we started with surface level questions: “Cross the line if you like football, cross the line if you like cats.” Everyone was giggling and looking across the volleyball court at their friends, smiling. But suddenly

“Cross the line if you have been affected by suicide.”

I watched as over half the students in that gym walked forward. My heart sank.

“Stay there if you were the one who has considered or attempted suicide.”

Too many of them stayed. I looked around at the people I loved, at the people I had told myself I had hated, all standing up there.

Soon we got into even scarier topics (if there were such a thing). “Cross the line if you or someone you know has faced sexual abuse.” “Cross the line if your family is struggling with money.” “Cross the line if someone who has ever said they loved you has hit you.”

As the questions came and went, I realized how ridiculously, incredibly fortunate I was. And as I continued to watch too many people I recognized crossing that line, I began to realize:

How many times had I passed by them in the hallway? How many times had I never bothered to simply say “hello”? How many times had I made fun of something they had done in class or on social media, without thinking about why they had done what they did?

Why had it taken me this long to see my peers as people, not just bodies filling desks?

After the activity we returned to our small groups, with nearly everyone in tears. And we opened up. I talked about what terrified me in my life, others talked about what terrified them in theirs. We discussed how sure, some problems were bigger than others, but that didn’t make them any less relevant. Not a single joke was cracked, only hands held and tissues passed. And that was okay.

We returned to the bleachers and discussed. We discussed what we didn’t know about other people before, we discussed what we had opened up about ourselves that we had never opened up about before. Some even admitted to the wrongdoings that they had done in the past. And no one spited them or felt angry towards them, we just smiled and felt proud that they had now repented.

We once again entered lighter conversations of where we wanted to travel to in the world or how many dogs we would own, but this time, it was more personal. Gone were the judgements of how ridiculous their goals were, because if they made this stranger–our new friend–happy, that was all that really mattered.

When the bell rang at 2:40, I left with a newfound respect for these incredible people. But now, it was all over.

And that’s what truly worries me about these types of programs. Sure, while you’re in it it seems as though everyone is affected and wants change. But once the bell rings and the day is done, it’s back to being surrounded by the 1900 other kids who weren’t a part of the program, who didn’t get the chance to bond and connect like you and your fellow group mates just did. Everything seems to go back to normal, the idea of humanizing these peers and understanding that Rocklin isn’t as idealistic and flawless as everyone builds it up to be becoming a thing of the past.

But if we really wish to see a change, to make all of our stories and our tears worth it, we have to make that conscious effort. Make the effort to look beyond the surface of someone’s actions or clothing, and try to find the deeper reasons as to why. Before assuming Rocklin is this ideal white suburbia where nothing happens, take a step back and realize that Rocklin isn’t just you, but a wide variety of people with a wide variety of stories.

Campus culture is easy to change if you just remember one thing:

It’s hard to hate someone whose story you know.