When she first came to the US in middle school, Ekaterina Dorozhkina spoke almost no English. That didn’t stop her first American friend from trying to teach her, though she could only communicate nonverbally. Dorozhkina’s friend would talk in English until Dorozhkina made a confused face. Her friend would try again but with simpler words. If Dorozhkina’s expression didn’t change, they’d pull out Google Translate.

“At first it was hard,” Dorozhkina, who moved to Rocklin from Russia in the eighth grade, said. “We kind of understood each other without words. Thanks to my American friend I learned a lot of new words.”

Since 2020, the number of English learner (EL) students at RHS has nearly doubled. A substantial portion of the newcomers are students from Russian speaking countries, many fleeing war or mobilization after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. In the 2020-2021 school year, there were zero Russian or Ukrainian-speaking English learners at RHS. This school year, there are 13. This makes Russian-speakers the second largest English learner group at RHS after Spanish-speakers.

“They’re not getting a lot of that really long, consistent language development.”

School staff were not equipped to deal with this sudden influx. While Whitney High School has a Russian-speaking aid, there are no Russian-speaking staff at Rocklin and no plans to hire any, said district English learner coordinator Sarah Soares. RHS’ EL program is “adequately staffed” as of now, she said. As it stands, Russian-speaking students are often placed in English Language Development (ELD) classes with Spanish-speaking and other English learner students with little direct language instruction.

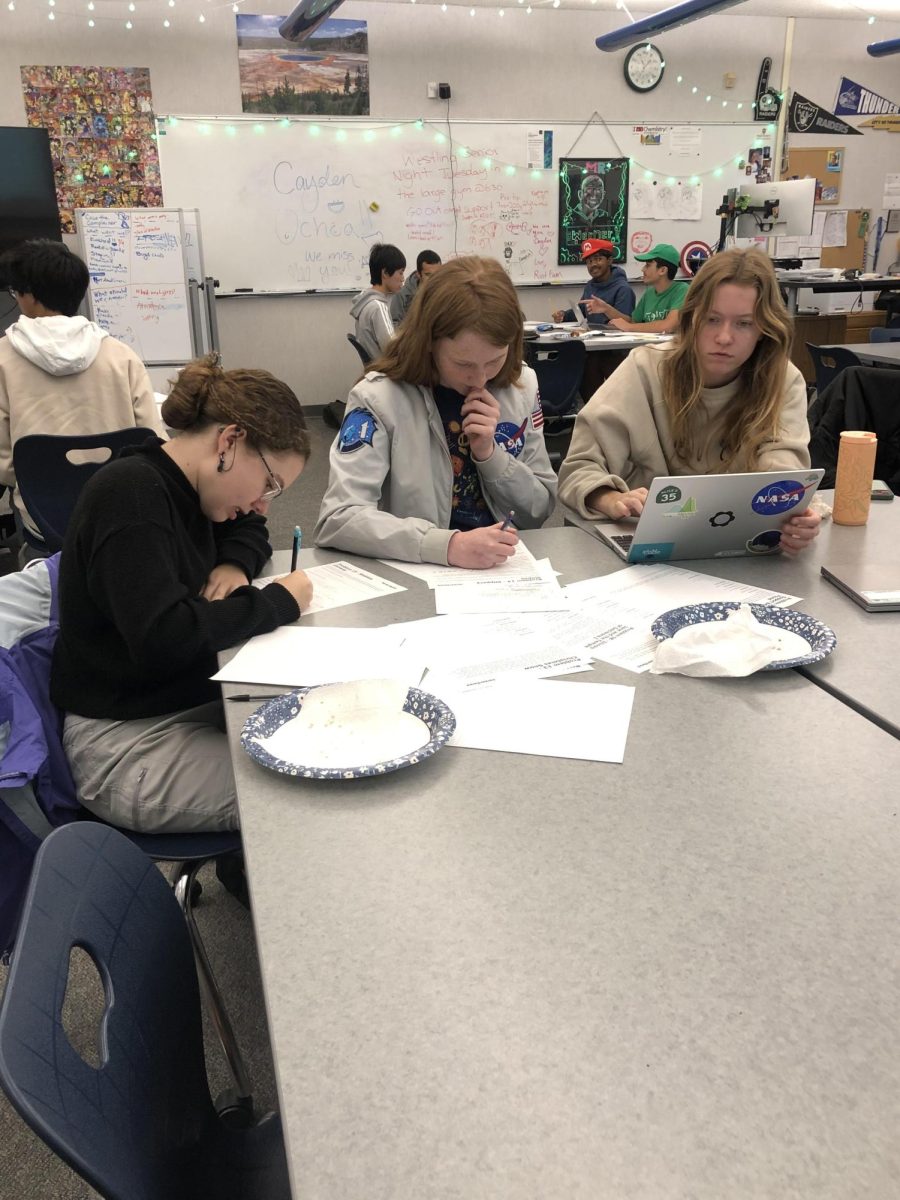

“You do the best you can with gestures being basic, or I have other students with the language help,” said RHS ELD teacher Adrienne Tacla. She said ideally the school would have a “newcomer program” to teach EL students the basics of English for at least half the day, but there simply isn’t the staffing for that. Instead, the school has simply added an additional section of ELD to accommodate the increase.

“They’re not getting a lot of that really long, consistent language development,” Mrs. Tacla said.

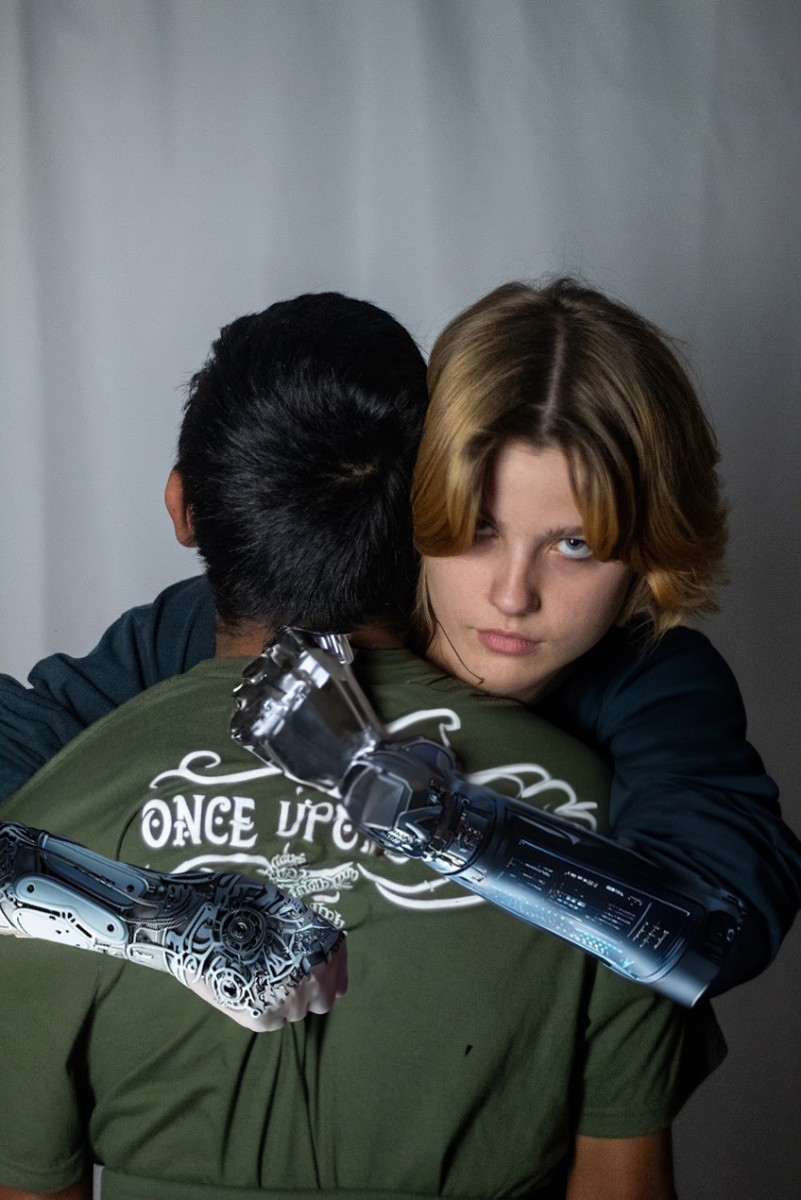

Junior Alina Turdubaeva came to the US in July 2023. Her brother moved first because of mobilization in Russia, and the rest of her family followed for better work opportunities. Born in Irkutsk, Russia, she had already moved over 5,000 kilometers to Moscow. But now she was moving to a new country with a radically different culture and language than her own.

Unlike Dorozhkina, Turdubaeva had learned some English from private courses and social media.

“I knew English a little, but it was hard to speak at first like to explain where I need to go or what I need,” she said.

During Turdubaeva’s first year at RHS, she took mostly ELD classes.

“Mrs. Tacla really helped me when I came, but for Spanish-speakers it’s easy because most of the teachers speak Spanish but not Russian,” she said.

Dorozhkina said she spent most of her time in her freshman and sophomore ELD classes sleeping. “We didn’t learn anything, they help you but we just kind of talked in class the whole time,” she said.

"I'm hoping at some point we'll get more support for our newcomer students, but until then, we kind of just do what we do and we try to do our best.”

Tacla relies on students who are more proficient in English to help those who are not. Students close to testing out of ELD classes are often one of the only ways teachers can communicate with Russian-speaking students. “They're usually very helpful, and I have students who are really good at teaching as well,” Mrs. Tacla said.

It can take anywhere from one to three years for newcomers to learn English to a level at which they are ready to take mainstream classes, depending on how much English they know coming in, she said. While the school does its best to get them to graduate with the credits they earned at other schools, it isn’t always possible.

“A lot of them have had high-quality schooling, but for some of them, if they come as a junior or senior and they don't have a lot of credits, then they may not be able to get a diploma,” Mrs. Tacla said.

Mrs. Soares said many Russian and Ukrainian-speaking students arrive with strong transcripts, so graduating them is usually not an issue. In addition, there are specific provisions in place for those who arrive later in high school to help ensure they can get their diploma, she said.

Though she knew almost no English when she came to the US in middle school, Dorozhkina now only takes regular classes, which she finds more interesting, she said. Unlike many EL students who eat lunch in Mrs. Tacla’s classroom and stick with other speakers of their language, Dorozhkina now has more English than Russian-speaking friends.

“There are more Americans who are much more interesting to talk to,” she said. “There are of course Russians who are studying hard but it is much more interesting for me to talk to people who care about learning.”

Talking with her friends has helped to improve her English, she said.

“I understand words, but when it comes to speaking, I forget certain words,” she said. “But when people speak to me I understand.”

She said that subtitles and extra time would help her and other English learners better keep up in mainstream courses.

Dorozhkina said that she wishes she could “read more English books.” Although the library has recently acquired books in Russian, she said she wants to be able to read them in English. She has an A in her language arts class, but usually has to read the novels in her native language, she said.

Often, Mrs. Tacla’s job is just as much about acclimating students to a new culture as it is teaching them. From Homecoming week to senior activities and sports, newcomers often have no idea how to navigate the American high school system, she said.

“There's a big cultural divide as well as a language divide,” she said.

The numbers of EL students at RHS have been slowly increasing against expectations, said Mrs. Tacla.

“It really depends on what's happening in the world,” she said. “We're tied to significant world events, and our population is affected by that. I'm hoping at some point we'll get more support for our newcomer students, but until then, we kind of just do what we do and we try to do our best.”

She said students should try to put themselves into EL students’ shoes.

“These kids are just like kids anywhere,” she said. “Some of them like school. Some of them don't like school. And then you have to think of some of them want to be where they're from. And that's hard.”