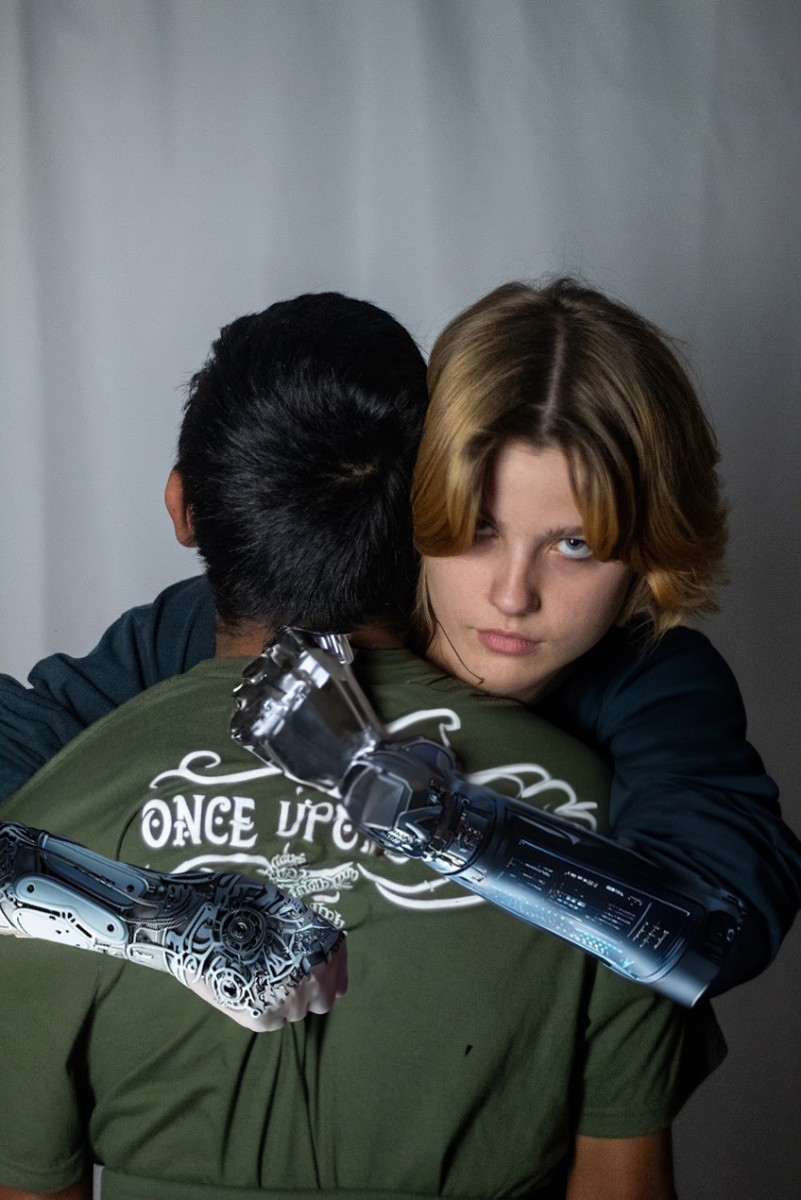

Uneaten fruits and vegetables are heaped by the dozen on ledges and in trash cans, jetsam from the lunch line. As lunch goes on, the piles only grow.

Each day at Rocklin High School (RHS), pounds of food are taken from the lunch line only to be immediately discarded. To someone unfamiliar with the regulations surrounding school lunches, this might seem like a puzzling and unnecessary source of waste — why do students take food they don’t plan to eat? The answer is in the law.

First passed by congress in 2010, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act requires students to take at least one half-cup of fruit or vegetables for a meal to be reimbursable. Rocklin USD nutrition services director Charles Douglas said the reimbursements are his department’s primary revenue stream. “If we’re in an audit year and the auditor comes out and they literally stand here and watch every kid get served, if they see a student that doesn’t take a half cup or fruit or vegetable, that meal doesn’t count. We don’t get paid,” he said.

“But at the same time, you’re forcing students to take things that they don’t necessarily want. And as an unintended consequence, what do you see? You see a lot of waste.”

Put in place to combat childhood obesity, particularly in low-income communities, the law has led to an uptick in food waste, according to Mr. Douglas. “And that’s what I like to call the unintended consequence, because we want to encourage [students] to take food and vegetables,” he said. “But at the same time, you’re forcing students to take things that they don’t necessarily want. And as an unintended consequence, what do you see? You see a lot of waste.”

A Harvard study frequently cited in support of this law found that the requirement to take at least one fruit or vegetable did not in fact increase plate waste in a sample of low-income elementary and middle schools. The study concluded that it accomplished its goal of increasing consumption of fruit and vegetables without the negative consequences that nutrition services directors across the nation had feared. While all this may be true, RHS, a relatively high income secondary school, clearly lies far outside of the narrow scope of this study.

Though Mr. Douglas has observed a positive impact on fruit and vegetable consumption among elementary school students as a result of this policy, he cannot say the same about high schoolers. Nevertheless, he recognizes that there isn’t much he or the district can do to change the status quo. Whether or not this policy has a positive overall effect nationwide, it is clear that, for the time being, it is here to stay. But it is also clear that, policy or no policy, food waste remains a significant issue in school cafeterias nationwide.

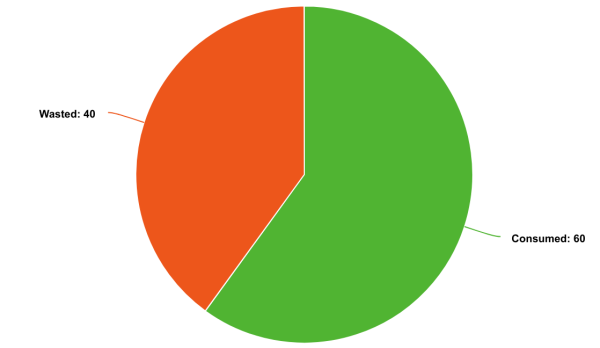

According to the same Harvard study, even before the new regulations, students discarded sixty to 75 percent of vegetables and 40 percent of fruits they were served; according to Mr. Douglas, RHS alone serves over 1100 meals a day. If RHS students discard anywhere near the same percentages of fruits and vegetables as the students in the study, this translates to an enormous amount of waste.

“There are students here that do not have three meals a day at home. The shared table has helped those students.”

So far, the school and district have implemented several strategies to reduce the amount of food waste generated each day. USDA permits the use of a share table to reduce food waste and encourage consumption of fruits and vegetables. RHS nutrition services lead Christina Thurman estimated that roughly 80 percent of what is left on the share table after meals is added back to the inventory, significantly reducing waste. However, not all food waste makes it to the table in the first place, said Mr. Douglas, and it is difficult to know how much of an impact it has. Still, Mrs. Thurman said, “There are students here that do not have three meals a day at home. The shared table has helped those students.”

According to Mr. Douglas, part of the reason that the policy has had a greater positive impact at the elementary school level is that there they can offer salad bars. “Typically when you get into the secondaries, middle and high school, salad bars typically don’t work there,” he said. Mrs. Thurman has identified serving fruits and vegetables that students like — sliced and bagged apples, grapes, bananas, and carrots, for example — as a way of combating food waste at RHS. “I believe we are finding a solution to food waste by offering fruits and vegetables and food that [students] will eat,” she said.