Banned Books: From “Black Boy” to the Bible

A celebration of our 1st Amendment rights.

September 28, 2016

If you’ve read the Bible, “The Great Gatsby,” or “1984,” you’re a criminal. All these books have been challenged, censored, or banned at one time for their explicit content.

“Black Boy,” the Bible, and “The Lorax” were all banned for their controversial ideas. “Black Boy” was decried by school districts nationally for its sexually explicit references and foul language. The Bible is the sixth most challenged book in America for its religious viewpoint, according to the American Library Association (ALA). Closest to home, Dr. Seuss’ “The Lorax” was banned by the California state legislature for defaming the logging industry.

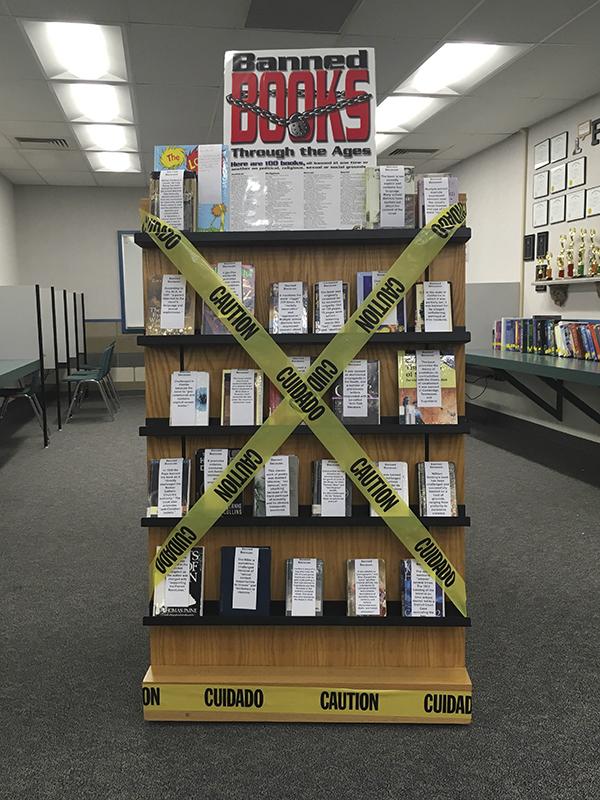

This week is Banned Books Week, a national celebration of our 1st Amendment rights, highlighting the history of censored books. The celebration’s purpose is to remind Americans that our prized freedoms of speech, press, religion, assembly, and petition has, historically, allowed for free collaboration and expression. When these rights are infringed, our open access to information is hindered.

Censorship takes place at all levels of society: from local school boards to the federal government. Often religious, ethical or moral issues are at the heart of the decision to ban a novel.

A common misconception is that book censorship is a trend of the past, but I can assure you it is alive and well. According to the ALA, there were at least 311 censored books in 2014, not accounting for the 70 to 80 percent of unreported censored novels. In 2015, John Green’s “Looking for Alaska” topped the banned book charts for its “offensive language, sexual content, and unsuitability for age group.”

As a student, a journalist, and a citizen, this is troubling. Why do strangers have the power to arbitrarily decide what I can and cannot read? My ability to understand the world in a greater context and enrich my learning should not be determined by a religious organization, a parental board, or a government entity.

Often, books are banned because they challenge the status quo. The book is socially unacceptable, challenges racial norms, or explores a controversial issues. Those censored books will further the realm of human understanding.

Charles Darwin’s “An Origin of Species” was banned for challenging the church’s belief in creationism, and Niccolò Machiavelli’s “The Prince” was banned for directly challenging the authority of the Roman Catholic Church. The books themselves weren’t banned because people knew they were radically right, but because they were intrinsically different.

In the words of Kofi Annan, former Secretary-General of the United Nations, “Literacy unlocks the door to learning throughout life, is essential to development and health, and opens the way for democratic participation and active citizenship.” But, reading itself would change nothing if every book was censored to be ideologically similar and culturally safe. Banning books is limiting the scope of human knowledge and criminalizing reading—and thus, limiting learning.